In the general elections held in Germany on September 26, the social democratic SPD took the lead, showing that the already existing trend of pluralization in the German legal political system will continue.

So, where does the women and their representation stand in all of this?

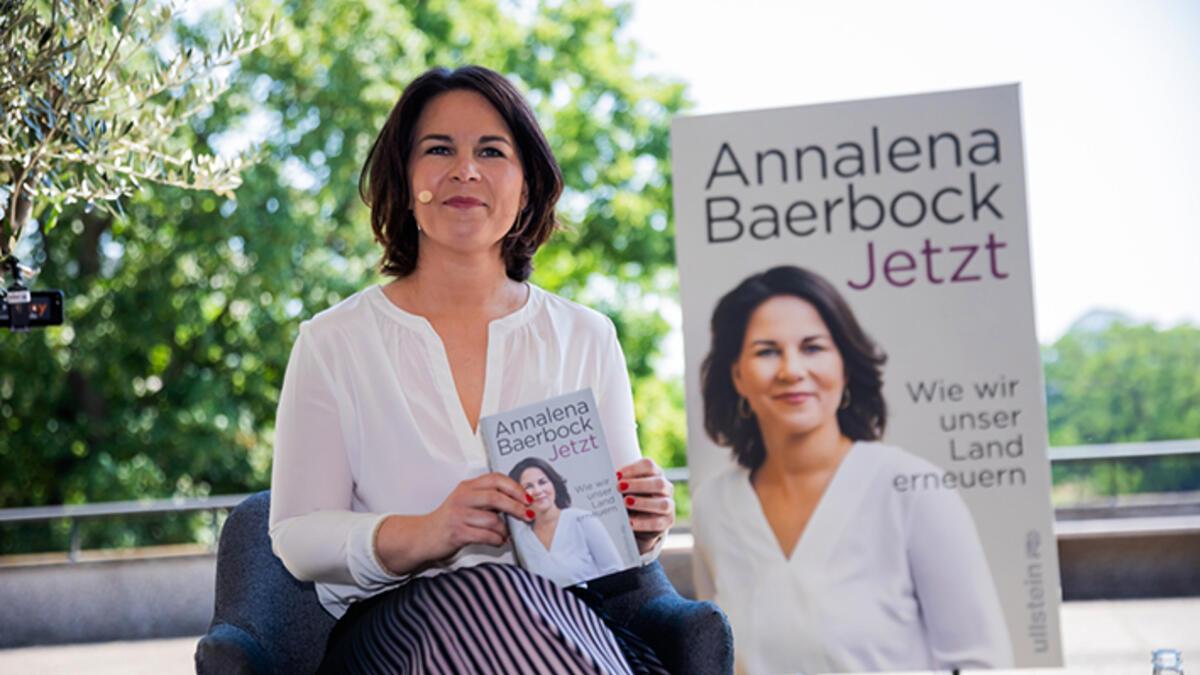

The analysis of journalist Emily Schultheis, known for her articles on European politics and the rise of populist parties, sheds light on this issue. Schultheis argues that the “rise and fall” of the Green Party Co-Chair and the party’s candidate for chancellor Annalena Baerbock is a symbolic example of the difficulties of being a woman in German politics.

Germany has left behind an election that will be heatedly discussed for a while, both within the European Union and in the world. In fact, the September 26 elections were not just general elections in many ways. On the same day, state elections were held in many cities, while in Berlin, in addition to all these, there was a referendum on rent increases and the current housing crisis.

Two parties competing in the federal elections, the centre-right CDU/CSU (a political alliance formed by Germany’s two Christian democratic parties, the Christian Democratic Union and the Christian Social Union), and the Greens, lost the chancellor seat to the social democratic SPD and its prime minister candidate Olaf Scholz.

Liberal FDP increased their vote, while the far-right AFD lost at least as many votes as liberals. Undoubtedly, one of the surprises of the election was that Die Linke (Left Party), the heir to the Democratic Republic of Germany, fell under the threshold, but thanks to three directly elected deputies, the party will be able to cross the threshold and enter the parliament. In other words, the 2021 elections show that the already existing trend of pluralization in the German legal political system will continue. So, where does the women and their representation stand in all of this?

The analysis of journalist Emily Schultheis, known for her articles on European politics and the rise of populist parties, sheds light on this issue. Schultheis argues that the “rise and fall” of the Green Party Co-Chair and the party’s candidate for chancellor Annalena Baerbock is a symbolic example of the difficulties of being a woman in German politics: “The candidate’s struggles reminded female politicians in Germany that even after 16 years of Angela Merkel, the country has a long way to go.”

A segment from the article can be read below:

Emily Schultheis / Politico

On a warm evening in early September, Annalena Baerbock took the stage on a packed city square here. There were just over three weeks to go until Germany’s general election, which will take place on Sunday, and around 2,000 people had come out to see the progressive, pro-environment Green party’s first-ever candidate for chancellor. “You can feel the change here on Wilhelmplatz,” Baerbock told the audience, to cheers and applause.

As she spoke, four young girls toward the front of the crowd climbed a metal divider to get a better look at the candidate. Baerbock, energetic with microphone in hand, occasionally referred to them in her speech: When a handful of right-wing protesters started shouting, she reminded them there were children present, and during her Q&A session, she came over and answered the girls’ question about how to live a more climate-friendly life. Over the course of the rally, other girls wandered over from their parents until about a dozen stood there, grouped together near the stage, eyes turned up toward Baerbock.

These girls have an experience of politics American girls don’t: They have never known a country in which a woman didn’t hold the highest office in the land. For the past 16 years, Angela Merkel has been a steady hand at the country’s helm and arguably the most powerful woman in the world.

But in Baerbock’s candidacy, they’re also watching a real-time demonstration that even in Germany — a country often held up as a model for embracing and re-electing a powerful woman leader — sexism isn’t easy to root out of politics. It can be difficult even to disentangle the two.

Baerbock was an early contender in the election, leading her two main rivals for several weeks in the spring — an unprecedented feat for the Greens, who have never before had a real shot at the chancellery. Since then, she has come under unrelenting attack for a series of off-the-trail missteps, including revelations of plagiarism and resume inflation, while male rivals have more easily sidestepped their minor scandals. She has also been the target of frequently gendered disinformation attacks, one of which featured her face photoshopped onto a naked woman’s body with a caption implying she was a sex worker. Along the way, Baerbock has faced more familiar examples of sexism, such as questions about whether she can balance the chancellorship with being a mother.

The Greens are now polling at 16 percent, behind the center-left Social Democrats and Merkel’s conservative Christian Democrats, and Baerbock is effectively out of the chancellor’s race. Baerbock herself has avoided speaking too explicitly about sexism in the campaign, though others close to her have been vocal on the subject. In an interview with POLITICO Magazine this month, she mentioned the connection but was cautious about blaming the attacks on gender.

“There are always going to be moments when, especially as people run out of real arguments, they hit below the belt — we know that about campaigning,” Baerbock said. “But in this election, there’s also been an element of hate and smear campaigning, that’s been exacerbated by social media, at times gender-based.”

Her candidacy has left German political observers wrestling with the question of just how open-minded Germany actually is when it comes to women leaders. Baerbock might be the second woman to run for Germany’s top office, but she’s the first to experience the post-Merkel climate for female politicians seeking the job. It’s a contradictory environment in which a female candidate is no longer a historic first and embracing gender is far more culturally accepted — but in which the winner will preside over a parliament that is still more than two-thirds male, more skewed than many of Germany’s European neighbors. And, at least for Baerbock’s supporters, it’s hard not to look at the substance and tone of the attacks on her and detect very different treatment than her rivals.

“One can’t say that Germans don’t trust a woman to do [the job of chancellor]. We had a first example,” said Franziska Brantner, a member of parliament from the Greens who led the party’s campaign in the state of Baden-Württemberg earlier this year. “But still, a female candidate is getting different attacks — and on a different level — than male counterparts.”

Female politicians in Germany are disappointed, but not surprised, that a country that has broken such a visible gender barrier still has so far to go.

“You would think that, with a female chancellor leading the government, things would have steadily improved for women in politics,” said Sawsan Chebli, a state secretary in Berlin’s city government who is running for the Bundestag as a Social Democrat. “I wish that were the case.”