Kavel Alpaslan and Lara Villalón’s article in Jacobin explores the intersection of labor activism, student protests, and the broader democratic struggle in Turkey following the arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu.

This article has been published in Jacobin. To access the original link click here.

In their recent article for Jacobin, Kavel Alpaslan and Lara Villalón explore the growing intersection of labor activism, student protests, and the broader democratic struggle unfolding in Turkey following the March 19 arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu. His detention has triggered widespread demonstrations, reflecting not only political outrage but also mounting economic frustrations shared across Turkish society.

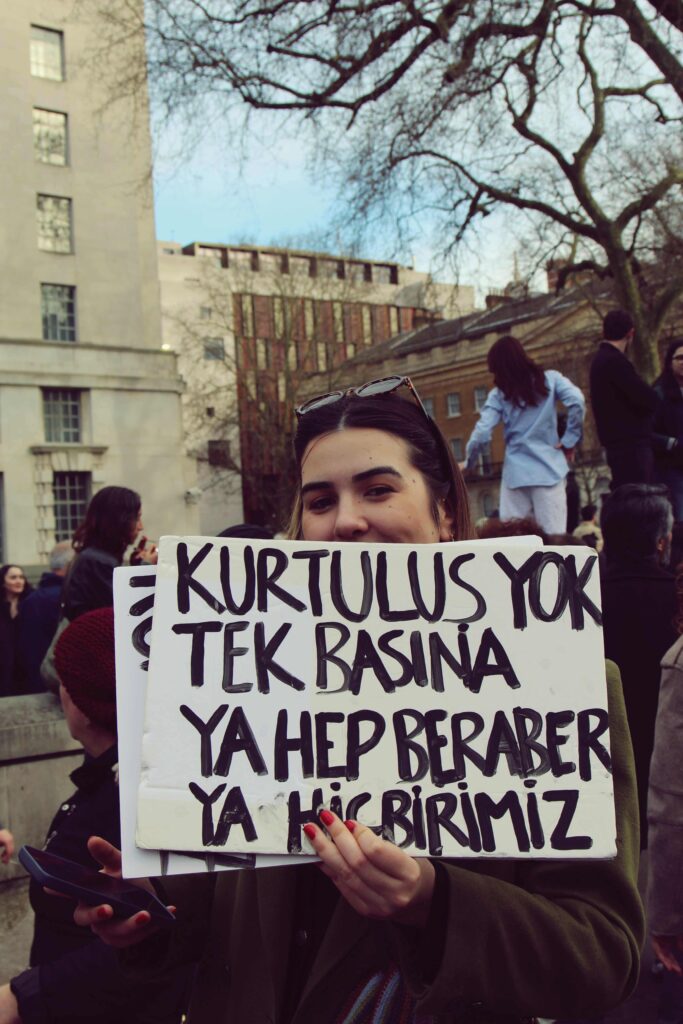

The article highlights how the arrest sparked immediate mobilization from university students, who have led demonstrations, campus boycotts, and marches. These protests expanded rapidly, addressing deeper social grievances like economic insecurity, erosion of rights, and the shrinking space for democratic participation. Slogans such as “Salvation lies in the streets, not in the ballot boxes” captured the broader mood of disillusionment with institutional politics.

Labor organizations, though facing structural and legal barriers, have also joined the fray. Başaran Aksu, leader of Umut-Sen, a socialist workers’ organization, called for a work stoppage on March 27-28, urging workers to make their absence felt as a form of protest. His call reflects a wider push for a general strike, with the goal of addressing the economic hardships and democratic restrictions affecting the majority of society.

Alpaslan and Villalón detail the historical context behind Turkey’s labor movement, noting that only 15% of the workforce is unionized. Legal restrictions, including a presidential ban on strikes since 2017, have hampered large-scale labor mobilizations. However, grassroots worker actions persist. The authors reference past movements like the 2015 “metal storm,” when over 150,000 metalworkers across several provinces organized mass workplace occupations, demonstrating the capacity for worker-led resistance despite structural obstacles.

The article also notes the active presence of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), Turkey’s main opposition party, during the initial phase of protests. CHP leader Özgür Özel addressed crowds gathered at Istanbul’s city hall, stating that the party could call for a general strike “when necessary” to counter government actions, signaling the CHP’s engagement with the unfolding democratic struggle.

Throughout the protests, university students have remained at the forefront. Facing rising tuition, housing costs, and limited job prospects, students have become a driving force in voicing both political and economic grievances. Their protests have gained support from labor groups such as Eğitim Sen, a major teachers’ union, as calls for greater solidarity between students and workers intensify.

Alpaslan and Villalón conclude that while the immediate spark for these protests was İmamoğlu’s arrest, the demonstrations reflect broader societal discontent. Economic hardship, lack of democratic freedoms, and the erosion of institutional trust are fueling a movement that may continue to grow. The authors suggest that the future of this movement could hinge on whether labor groups and workers join students in larger numbers, potentially opening a new phase in Turkey’s democratic and social struggles