Ayşe Kadıoğlu, Professor of Political Science at Sabancı University, argues that we are entering a new Zeitgeist marked by a turn inward and a growing acceptance of authoritarian thought, a spirit that recalls the rise of European fascisms. This mindset, she warns, is seeping into all areas of life, from gender relations and popular culture to art and the everyday.

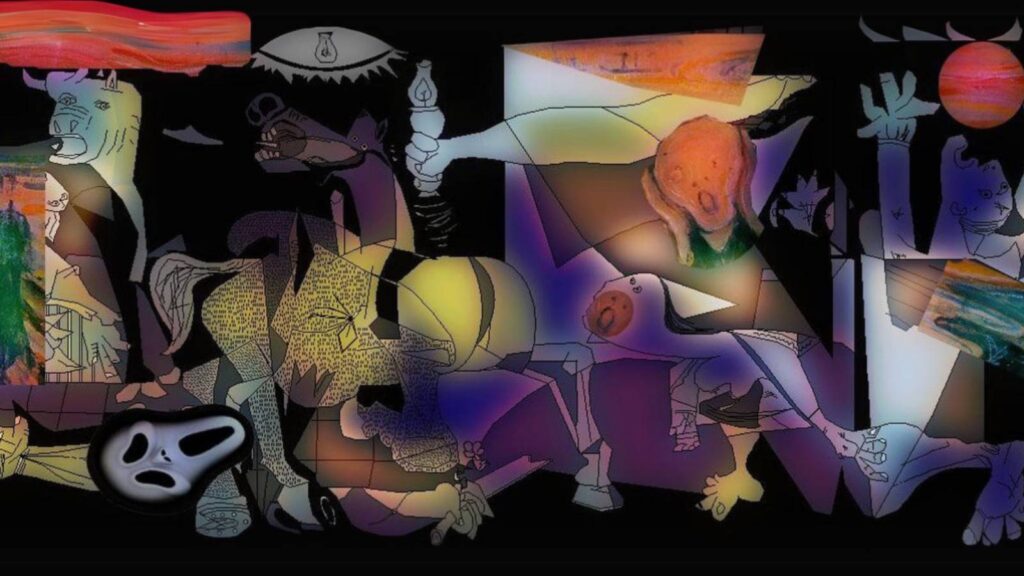

Visual: Joel Ormsby/Flickr, CC BY 2.0

In a reflective and critical essay, Professor Kadıoğlu walks us through how being self-sufficient is an approach that humanity has emphasised throughout history, and in Ancient Greek, this has been called autarky. Living self-sufficiently has been seen, both historically and today, as a marker of a dignified life. Of course, the reality is not quite so simple. In truth, human beings are social creatures, and people need one another.

Kadıoğlu contends that relationships with others are increasingly structured not around dialogue or mutual recognition but around the drawing of sharp boundaries. She observes that people now seek closeness with those who are similar to them and turn away from those who are different. Instead of engaging across lines of identity or belief, many are opting to cancel or erase difference altogether, rendering it invisible. In this cultural climate, Kadıoğlu believes that bridge-building is seen as outdated, while boundary-marking and retreat are viewed as both pragmatic and desirable.

She expresses concern about what this means for democratic culture. The democrats she once knew, she recalls, were curious about difference and committed to forms of coexistence that allowed for diversity. That commitment, she warns, is fading. Today, the pursuit of self-sufficiency extends beyond politics into everyday life. Kadıoğlu points to the growing number of individuals who are leaving cosmopolitan, immigrant-rich cities and choosing to relocate to the countryside. This movement, in her view, reflects a desire to withdraw from complexity and difference. Many take pride in growing their own food or drawing water from their own land, seeing these acts as symbols of personal autonomy and dignity.

Although she does not claim that self-sufficiency necessarily leads to hostility, Kadıoğlu insists that it carries a strong anti-cosmopolitan dimension. However, when scaled up to the level of state politics, she argues that it produces a more dangerous outcome. Autarky, she believes, has become the defining spirit of the current moment. It is shaping the language of domestic politics and dominating international discourse. According to her analysis, states that embrace inwardness are more prone to conflict and confrontation.

Kadıoğlu reflects on the fact that people did not always assume the world revolved around themselves. There was once, in her view, a greater openness to difference and a stronger willingness to engage with others across lines of identity. The autarkic mentality that has taken hold, she argues, leads to an erosion of empathy and an inability to see the humanity of those who are different. This, she suggests, helps explain how governments and citizens in the United States and across Europe can remain silent in the face of atrocities such as the genocide in Gaza. Some even offer unconditional support to the Israeli state, despite the human cost.

Yet Kadıoğlu also draws attention to those who continue to resist this spirit of indifference. She highlights students who risk their education, individuals who give up careers or leave their families to support Gaza, and political actors who refuse to remain silent. These people, in her view, represent a powerful counterexample to the dominant trends of withdrawal and self-protection. They serve as a reminder that human dignity and solidarity have not entirely disappeared. Kadıoğlu holds onto the hope that history will record their actions as meaningful contributions to what remains of our shared humanity.

Find the full article in Turkish in this link.