Gülseren Onanç reflects on how the women’s movement in Turkey is debating masculine violence and discourse on media along with the efforts of the incumbent to establish religious domination over women’s liberties.

Gülseren Onanç

It has been argued by some that feminists are faced with a dilemma today. The dilemma is the existence and the number of women who advocate and act in ways that restrict women’s liberties and reproduce masculine discourse and violence.

This “dilemma” came to my mind when I saw the horrendous scenes at a reality show that exposed a young woman without her will, intending to publicly shame her for having a relationship with a married man. Esra Erol, the host of the reality show broadcast on Turkey’s ATV channel, shouted, blamed, scolded an 18-year-old woman live in the studio, and tried to give her a “moral lesson.” Although the young woman did not want her face to be seen, she exposed the young woman on live television.

This embarrassing public event led us to look at where masculine violence comes from.

In her article, Berrin Sönmez argued that “Gender-based violence is a phenomenon that should be defined not by the gender of the perpetrator, but by the mentality of the perpetrator.” Sönmez draws attention to the masculine violence perpetrated by women and underlines that what lies behind the violence is not their gender but mentality.

Similarly, Zehra Çelenk asked the question: “How is it that the person who was least affected by all this moral questioning and who survived all without a scratch is Kadir Akkoyun, the 40 years old, married and father of two?”

She demonstrated how it is in our cultural codes to blame the woman, not the system,”

I believe that this discussion of masculine violence, which develops over the female body and sexuality, should also be viewed by taking into consideration the attacks on secularism created by the current political climate in Turkey.

Women are being targeted under this process.

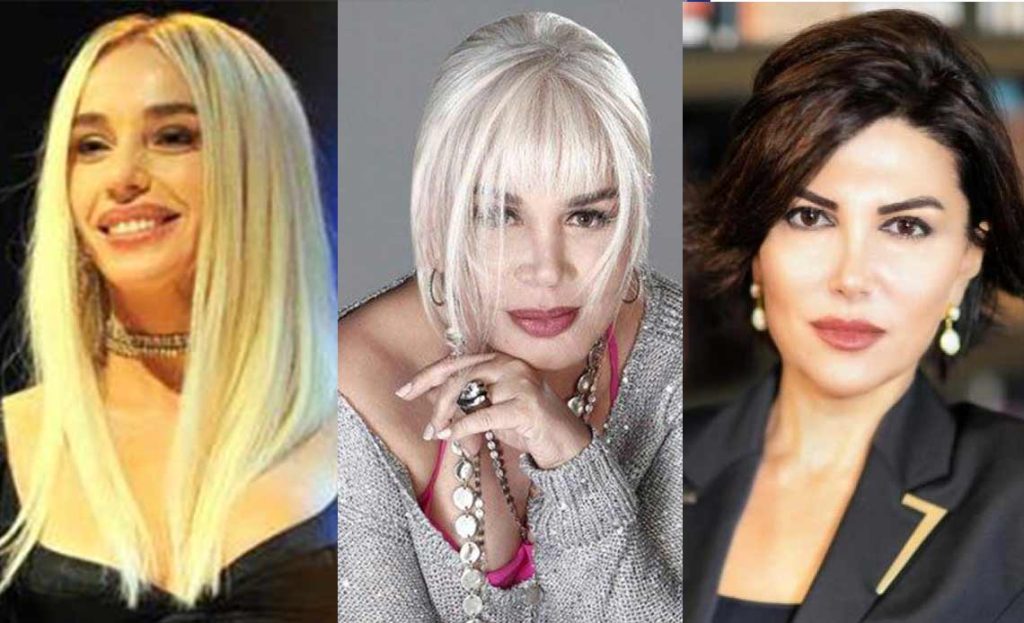

Last week, prominent singer Sezen Aksu was accused of “insulting religious values” by a group that the president was a part of, using the lyrics of her song as an excuse.

Pop singer Gülşen’s stage clothes and dances were targeted. She was subjected to heavy accusations, especially from some of her colleagues, on social media and television programs due to her clothing.

Recently, HDP Istanbul deputy Oya Ersoy was targeted because, in her speech at the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, she made this statement against the incumbent: “You are trying to revive the religion-based social order by taking us 1500 years back. We women have learned that we can be free. We have no intention of going back 1500 years.”

She has been accused of “insulting ancestors, religion, and the provisions of religion.”

All these cases demonstrate the efforts of masculine politics to establish religious domination over women’s liberties.

Mine Melek says that women’s struggle for a secular life is a daily and feminist act of self-defence. She criticises official secularism, saying it also makes possible new aggression denounces women’s autonomous existence, lives and rights, and advocates feminist secularism instead. She says that a secular life will only be possible by securing the material, political, cultural and ideological conditions of equality of women and men in all fields. This is possibile by reconstructing the public-political sphere and the private sphere as an arena of equality and freedom free from patriarchy, which is legitimised by religion.

Furthermore, Mine Melek states that the generation of women’s struggle that is now developing worldwide uses the slogan “secular state free bodies.” It seeks to be constrained by all kinds of religious ideologies, rules and culture. Her principle of feminist secularism is the elevation of the principles of women’s freedom struggle to the level of a common political-ethical principle that builds a new society/life.

To end, the women’s movement in Turkey has been building the networks and the quest to overcome the threats that are posed due to masculine violence very strongly. The women’s struggle for equality, which has been fought all over the world for centuries, gained momentum in our country with the increasing mobilisation of the women’s movement in the aftermath of a repressive military coup that took place in 1980. The valuable pioneers of this movement formed political, academic and organisational networks. If we can still talk about women’s rights in Turkey today, we owe it to the brave, combative and organised feminist women’s movement that resists political Islam.