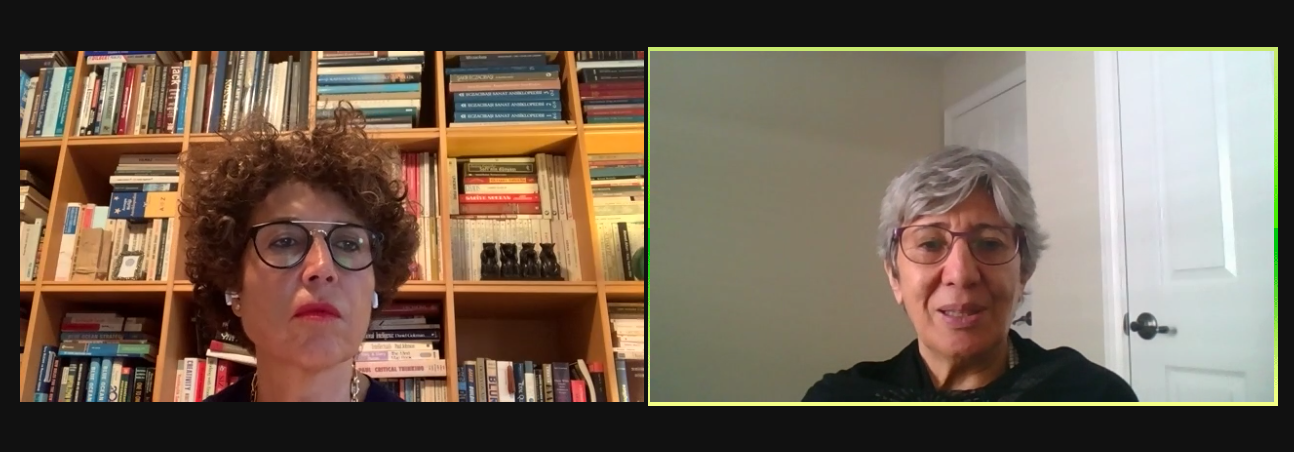

We interviewed human rights activist and former Minister of Women’s affairs Sima Samar on recent developments in Afghanistan. She states the international community could play a role to fight against the oppression of Afghan women under the rule of the Taliban. She also underlines that this would not be a ‘favour’ for Afghan women but that it is their ‘responsibility’:

“My call on the international community is that, they are not doing a favour for us when they stand for the rights of women and protect human rights. It is their responsibility. It is their job. And they have to do that.”

Sima Samar is a doctor for the poor, an educator of the marginalised and a human rights defender from Afghanistan.

She has established and nurtured the Shuhada Organization that, in 2012, operated more than 100 schools. At the time, Shuhada also ran 15 clinics and hospitals dedicated to providing education and healthcare, particularly focusing on women and girls.

Samar served in the Interim Administration of Afghanistan and established the first-ever Ministry of Women’s Affairs. She chaired the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission that holds human rights violators accountable, a commitment that has put her own life at great risk.

Samar is one of the most influential people in the world, advocating for women and minority groups.

Her humanitarian pursuits have not come without serious risk to her life, and yet Samar has never deterred her efforts. She once stated, “I’ve always been in danger, but I don’t mind. I believe that we will die one day so I said let’s take the risk and help somebody else.”

She is now in the US, still in shock at what’s happening in Afghanistan, not knowing what will happen next. But she still has hope.

“I don’t want talk about the Afghan women as victims always. They are brave, they are strong, they watch the destruction of their houses, killing of their husbands, brothers and fathers and their sons and daughters. But they still survive. But we need to recognise their suffering and that is what we need to do.”

Her work on human rights and social work is recognized around the world. Gender discrimination at early ages in her life was commonly prevalent. She was a girl from a minority group in Afghanistan. She started earlier to search for ways to promote equality. She talks about how feminism is a part of her work as follows:

“For me feminism is to protect the dignity of human being. Being woman, being third gender, fourth gender, being a man. We all have to live with same dignity. Particularly I want to say here as a Muslim, that we do believe that everybody is created by God. People who are opposing women’s existence or trying to put women in an inferior position, is trying to fix the mistake of the God?”

As a woman involved in Afghan politics and bureaucracy, she faced a lot of difficulties since women have always seen as second-class citizen in Afghanistan:

“Its quiet difficult to be involved in politics as a woman because you are dealing with people who mentally are not prepared to except women equally. They always think everything should not be related to women. But in fact, everything is related to women. In Afghanistan, after the coup d’etat in 1978 and the invasion of USSR, men were always important, because they were carrying the guns. Women in Afghanistan were suffering because they were not involved in creating the conflict. But they were the ones who were subjected to discrimination because when there is a conflict and insecurity, of course women are more vulnerable. Even a family member, who believe in equal rights between men and women, can try to protect you. Under the umbrella of protection, they restrict your movement. They restrict your freedom of expression for example. There was a lot of pressure on women in Afghanistan. And then when I was in politics, I am still in politics, they usually see you as a second-class citizen.”

“You need to fight for every single thing. This was said in a public speech: ‘If you can not prove the allegation, than you have to wear a scarf.’ You can see the mentality. They talk about your clothes, they talk about your appearance, they talk about your hair, they talk about your talking, your style and then without any kind of accountability or any kind of moral responsibility, they blame you are this and that.”

Stating that the silencing of women’s voices in the negotiation table played a part in the current outcome in Afghanistan, she also thinks the underrepresentation of women in the interim government had been a mistake:

“I think, not only silencing the women but also giving small number of seats to women in the government who is obligated to the international treaties, was not a good move. They were not really listening anybody, particularly women.”

Her message to Taliban is that, “they can not ignore the half of the population.” and that their denial is not going to change anything.

She thinks the international community could play a role to fight against the oppression of Afghan women under the rule of the Taliban. But she underlines the fact that this would not be a ‘favour’ but that this is their ‘responsibility’:

“My call on the international community is that, they are not doing a favour for us when they stand for the rights of women and protect human rights. It is their responsibility. It is their job. And they have to do that.”

She also has a message for the neighbouring countries on how they should position themselves regarding the Taliban:

“So a problem for Afghanistan is a problem for humanity. We like it or not, it will reach other countries. So my call on the regional government and neighbouring countries is that we cannot choose our neighbour, it’s beyond our choice. But we can choose to live with peace with our neighbouring countries and they should not forget that the problem in Afghanistan would reach them. I keep saying that, if you set your neighbouring house on fire, the fire will reach you. If the fire does not reach you, the smoke will reach you and make you cry. So that’s why neighbouring countries should be aware that it is a problem and that should be solved in favour of human dignity.”

She sees the role of the Turkish government as key to protecting Afghan women and girls against Taliban’s oppression.

“The Turkish government can play a stronger role because they are Muslim and they can have influence, so I propose that they should be engaged with them but they should not negotiate on the principles of human rights and women’s rights. Engagement is different than full recognition. Engagement should bring some positive changes.”

“I think they should say as a Muslim that everybody is born with dignity and they have to respect that. Education is key. It is not a luxury, it’s a basic human right. Educated women can be a better Muslim, than uneducated women. It is clear. So if they really want good society with good fate, we should educate women. As I said, education is not a luxury. It is a hadith. The prophet said that every Muslim has to get education even it is in China. In those times, means of transportation were different, of course. He did not say it is only for men. And the first message to prophet was ‘read.’ That did not say only men read.”

Finally her recommendation for activists, feminist members of the women’s movement in Turkey who are now searching ways to show solidarity with Afghan women is to support education programs in Afghanistan:

“Stand with us. Because if a small nail of women hurts, it bothers everyone. The second thing that we should all do is to support education programs in Afghanistan if you can. You can raise funds for local NGO’s.”